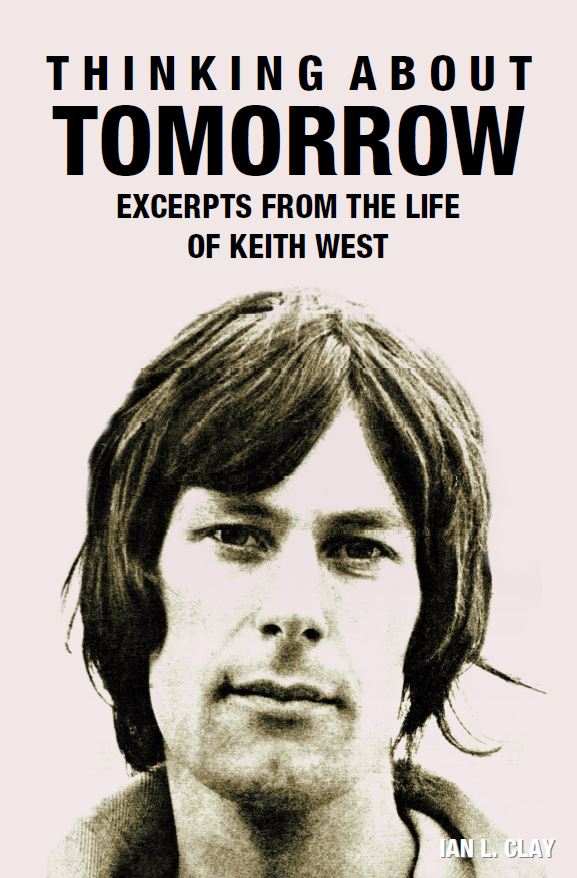

An excerpt from Chapter 12 of: Thinking About Tomorrow – Excerpts from the life of Keith West

*

The idea for the song that was to define Keith West’s professional career, in the mind of the general public at least, supposedly came from a dream which Mark Wirtz had in December 1966. ‘I saw this grocer named Jack, who was taken for granted by his village,’ said Wirtz in an interview in 2008. ‘He was only appreciated when he died – mostly by the children of the town who had taunted him when he was alive, but who loved him dearly and now missed him.’

As Keith points out, as gently as possible, ‘I wrote all the lyrics and, therefore, many elements of his inspired dream simply weren’t there at the beginning, especially the children’s section. But Mark, over time, and probably through telling the story repeatedly, has increasingly taken ownership of the entire narrative of the song.’

In reality, the involvement of both Keith and Mark in Excerpt from a Teenage Opera would be equally as important. Their combined strengths of lyrics and music, hip profile and classical training, a great singer and a killer hook, lots of studio time and a certain ‘throw it all at the wall’ approach to production, all combined to create a unique chapter in pop history.

As rock and roll ideas go, on the surface it was not the most promising concept. Still, Wirtz had got himself into a position where he was an in-house producer and arranger for EMI, and therefore had a certain latitude to pursue his own projects, without necessarily seeking the permission of his paymasters.

The antecedents of the song, and indeed Wirtz’s professional standing, go back to early January 1966 where Wirtz, a German musician with wide ambitions and interests from classical music to pop and rock, experimented with his vision by writing and producing A Touch Of Velvet – A Sting Of Brass under the name Mood Mosaic. His vision sounds simple, ‘To create movies on record’, but when explained, the concept becomes more nebulous; this lack of clarity would eventually cause problems for both Keith and Mark further down the line.

Never one to undersell his ‘genius’, Mark Wirtz’s explanation of his vision [in his own words] takes some swallowing: ‘Sonic, sensually graphic movies which, projected on the big screen in the listener’s mind and heart, would touch the audience into an experience as seen through the eyes of their own imagination, viscerally interpreted by their own unique emotions.

‘A Touch Of Velvet [the musical portrayal of a lovemaking event] was the original, primitive prototype of what I aspired to. A recording which, much like making a movie, made the musical experience the star, rather than a featured artist whose image and typical style would limit the freedom and possibilities of instrumentation and sound concepts.

‘My idea was to select all participants in my movies on record, just like casting actors and technical crew in a film.

‘My vision didn’t stop there. In order to have the same freedom which you have in moviemaking by shooting different segments in varying locations, with different characters, I implemented a method by which I recorded my movies on record in separately recorded scenes that I would later edit, cross-fade and ultimately melt together into a seamless whole. This method drove musicians and sound engineers crazy at first, until they heard the finished result – which they were so impressed by that they changed from being indignant opponents to enthusiastic fans and partners.’

Keith cuts through the pomposity of Mark’s statements saying, ‘Mark’s opinion of himself and his vision is somewhat overblown. Many things Mark professed to invent were not new either. Phil Spector, The Wall of Sound, The Shangri-Las, The Leader of the Pack, Brian Wilson, Pet Sounds, and the wonderful Jimmy Webb, had all been doing it for years.

‘Also, how is it possible to create a movie into a recording format? Asking the record-buying public to imagine pictures, or actual scenes, whilst listening to a piece of incidental/background music is where he was heading until the penny dropped and he had to change tack.

‘Honestly, I was not too impressed with most of his work. The two songs I wrote with him stand out by a mile as being the pinnacle of his production and arranging skills. We fell out eventually, and it came to a head with the track Sam.

‘It was my face on the record. I was the artist with the sole task of promoting the song. Listening to the original mix being played back at Abbey Road, I was thinking to myself it’s over 30 seconds before I start to sing, there is no chorus, so when I finish the last verse I have to wait approximately two minutes until the fade. That is a very long time in TV-land as anyone will tell you but, as it happens, the record was over 5 minutes long and no radio station or TV show would give it that much air time back in 1967. So, I hardly ever performed it.

‘Another bone of contention was the B-side, A Thimble full of Puzzles. As I was the artist, I expected to perform on both sides of the record and had written a couple of songs with Ken Burgess. It was not to be, sadly. I was railroaded. Even worse, when I listened to this track, I couldn’t believe how awful it was; it’s elevator music at best. I made up my mind instantly that I had to jump ship.’

A Touch of Velvet was accepted and released by EMI and achieved a decent amount of airplay as well as becoming the theme song for Radio Bremen’s show Musikladen. It was also used by some radio stations and DJs in the UK as idents, notably Dave Lee Travis on Radio Caroline. This small success gave Mark the opportunity to work on other projects and allowed his work to be heard by a wider circle of industry figures, one of whom was Kim Fowley.

Enshrined in rock folklore as the exploitative Svengali figure behind 70s all-girl group The Runaways, Fowley (in reality) has an extended pedigree as a publicist, songwriter, and producer. His credits include working as a publicist for P.J. Proby as well as writing songs for Frank Zappa, Warren Zevon, Kiss, and Alice Cooper, and producing albums for The Runaways and Gene Vincent.

Mark Wirtz remembers Kim, ‘He was taken with my production and arrangement of the Beach Boys’ tune I’m Waiting For The Day for the female artist Peanut. He not only hired me to produce and arrange several tracks for him but quickly became my champion and tutor as much as my hero. I was mesmerised by Kim’s flamboyance, unique thinking, reckless courage and utter disregard for music business convention, or protocol.

‘To me, Kim was the eternal, paradoxical commuter between the gutter and esoteric supremacy – a pig and a saint, a fool and a genius – he truly personified the ultimate spirit of Rock’n’Roll.

‘One of Kim’s many idiosyncrasies was his habit to preface virtually every noun with the adjective ‘teenage’. He would catch a ‘teenage’ taxi to a ‘teenage’ restaurant where he would order a ‘teenage’ steak before making his way to a ‘teenage’ studio to cut a ‘teenage’ record.’

It was an idiosyncrasy that would have a dramatic effect later in Mark and Keith’s collective history.

While planning to join Fowley in the USA, Wirtz was contacted by EMI’s product manager Roy Featherstone, at the behest of their head of A&R, Norrie Paramor, and offered a contract to join EMI as a producer with virtually unlimited creative freedom. Unable to resist, he accepted and cancelled his plans with Kim Fowley.

EMI’s offer to Mark came with a £30.00 a week wage, a 1% royalty, plus basic arrangement and conducting fees in accordance with musicians’ union terms. Soon afterwards, he signed an exclusive publishing deal with Tony Roberts and Ian Ralfini at Robbins Music as a composer/writer… not realising that his contract with EMI had included all of his publishing rights! This mistake would have more than a few ramifications in the next few years. Complicating matters further was that Mark had already signed a publishing agreement with Ardmore and Beechwood.

While the creative licence Mark had been granted at EMI was ahead of its time, his frustrations with the antiquated technology and working practices at Abbey Road (which have been covered in the My White Bicycle chapter of this book) remained. He recalls, ‘All in all, for better or worse, no matter how many grievances and frustrations I initially felt working at Abbey Road, there was no point in complaining, let alone attempting to seek refuge in another studio. Abbey Road was the only game in town for us – all EMI producers were contractually bound to work there exclusively. In terms of history, that curse turned out to be a blessing. Because of all the prevalent challenges and limitations, and our experimentation and inventiveness in overcoming them, the resulting music was among the most creative and profound in pop music history.’

*

Read more about this amazing story: